The Florida panther symbolizes what is left of natural Florida and is a guiding force behind much of the Florida Wildlife Federation’s work. This iconic species was one of the first animals listed under the Endangered Species Act. Today, they remain one of the most endangered mammals in the world and the most endangered cat in North America.

The Florida Panther

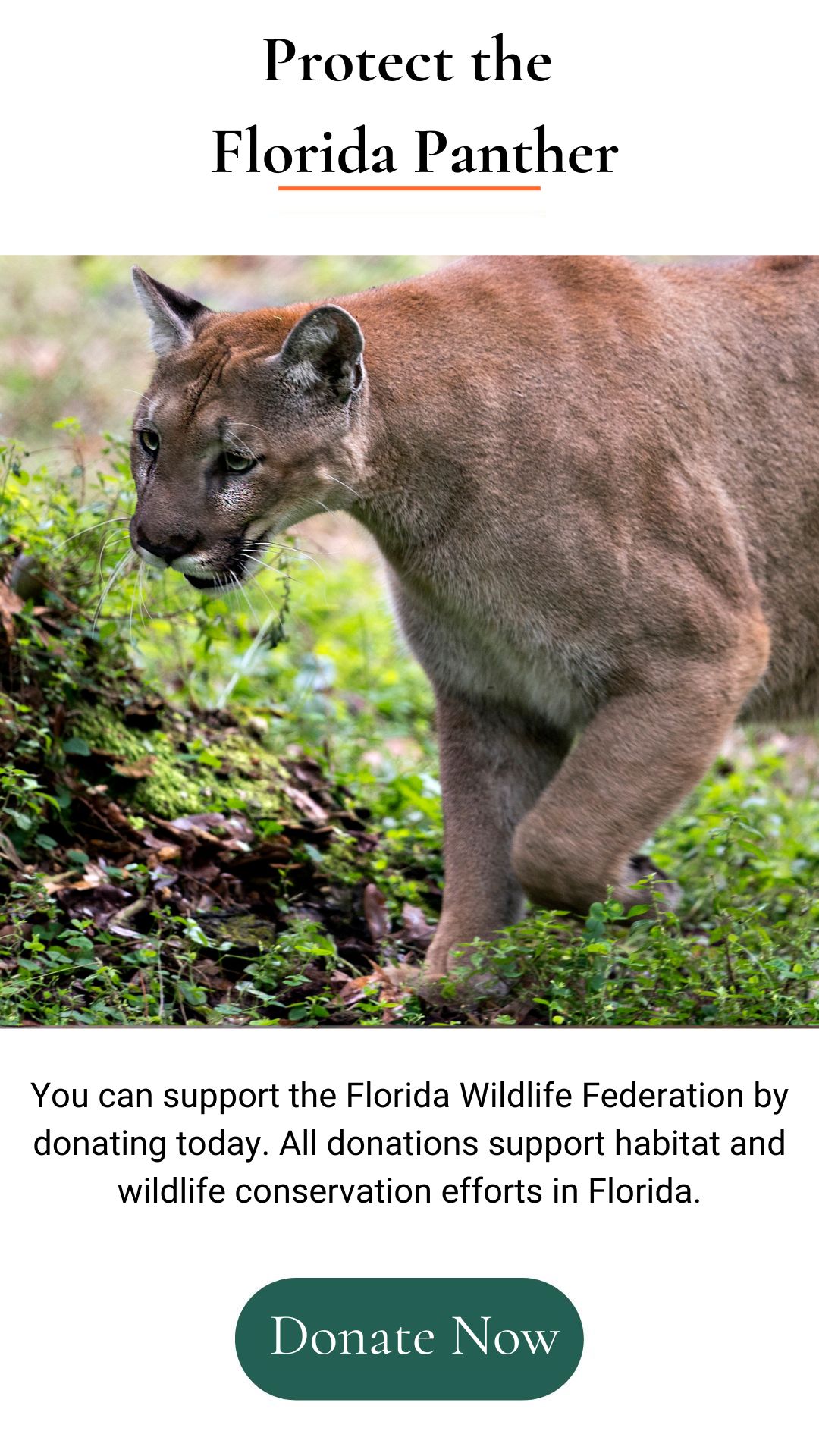

Protecting the Florida Panther

The Florida panther (Puma concolor couguar) is a North American cougar found in South Florida’s hardwood hammocks, pinelands, and swamps. As the last breeding population of its subspecies east of the Mississippi, it remains one of the most endangered mammals in the world and the most endangered big cat in North America.

- Habitat: Forested areas, pinelands, tropical hardwood hammocks and mixed freshwater swamp forests

- Population: Estimated at 120-230 individuals

- Conservation Status: Listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1973

Today’s Challenges

Once found across the Gulf Coast states, the Florida panther now survives only in southwestern Florida. As human expansion continues, suitable habitat is rapidly disappearing, intensifying these threats that put the species at risk of extinction.

- Habitat Encroachment: The expansion of urban and agricultural developments infringes upon the panther’s natural habitat, limiting their ability to roam freely and disrupting vital ecosystems.

- Population Constriction: With a small and isolated population, Florida panthers suffer from genetic stagnation, increasing vulnerability to diseases and health issues. Their restricted movement also heightens the risk of fatal collisions with vehicles, which is currently the leading cause of panther mortality.

- Infrastructure Barrier: Existing roads and highways slice through panther territory, acting as formidable barriers to their natural expansion. These man-made obstacles sever vital connections between habitats, further isolating panther populations and hindering genetic diversity.

Conservation in Action

FWF has a long history of engaging in panther protection. Through tireless advocacy and on-the-ground initiatives, we continue to play a pivotal role in protecting the panther’s habitat, advocating for stronger regulations, and raising public awareness about the importance of preserving this unique species.

Our current efforts focus on advancing practical, science-driven solutions and making panther recovery a priority at every level of government.

This includes:

- Protecting the last remaining habitat in Southwest Florida through careful vetting of proposed development projects with proper public engagement and scientific rigor.

- Expanding the current range to the panther’s historical range of the Southeastern United States by advocating for public and private land conservation and ensuring habitat connectivity through wildlife crossings on existing and proposed roadways.

- Reintroduce populations in science-based priority sites across the Southeastern United States.

Learn about the Florida Panther

Florida panthers are spotted at birth and typically have blue eyes. As the panther grows, the spots fade, and the coat becomes completely tan, while their eyes usually take on a yellow hue. The panther’s underbelly is creamy white, and it has black tips on the tail and ears.

Florida panthers cannot roar, and instead make distinct sounds that include whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. Florida panthers are midsized for its species, smaller than cougars from Northern and Southern climes, but larger than cougars from the neotropics.

Adult female Florida panthers weigh 29–45.5 kg (64–100 lb), whereas the larger males weigh 45.5–73 kg (100–161 lb). Total length is from 1.8 to 2.2 m (5.9 to 7.2 ft), and shoulder height is 60–70 cm (24–28 in). On average, male panthers are 9.4% longer and 33.2% heavier than females because they grow at a faster rate than females, and for a more extended period.

The Florida panther has faced a long and difficult road to recovery. Once roaming across the southeastern United States, its population plummeted to fewer than 30 individuals by the 1970s due to habitat loss, hunting, and genetic isolation. In 1967, the species was listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, later reaffirmed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Over the past several decades, conservation efforts, including habitat protection, the establishment of wildlife corridors, and genetic restoration programs, have helped stabilize the population, which is now estimated at 120-230 individuals. Despite these efforts, the Florida panther remains one of the most endangered mammals in North America, and continued action is needed to ensure its survival.

FWF Involvement:

- The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) introduced the Florida Panther Conservation Plan in 2024 as a collaborative effort between FDOT and various stakeholders, designed to mitigate the impacts of transportation projects on panther populations and their habitat.

- Helped to halt the 2022 MCORES plan to construct three new toll roads from Collier County to the Georgia state line.

- Worked with FDOT to install wildlife exclusionary fencing along nine miles of Alligator Alley along I-75.

- Legally challenged Collier County for not doing more to prevent urban sprawl from destroying panther habitat.

- Prevented the removal of Florida Panther 260 (FP 260) from the wild into captivity for preying on cattle in 2022.

- Successfully argued that the few remaining Florida panthers should be placed off limits to hunters in 1958.

The biggest threats to the Florida panther are habitat loss and fragmentation, which have drastically reduced the species’ range and forced individuals into smaller, isolated areas. As human development continues to expand, vital panther habitat is being lost or divided by roads, neighborhoods, and agricultural land. This not only limits the space available for panthers to hunt and breed but also increases the risk of dangerous human-wildlife conflicts.

One of the leading causes of panther deaths is vehicle collisions. As panthers are forced to navigate roadways in search of territory, prey, or mates, many are struck and killed by cars. Wildlife crossings and fencing have helped reduce some of these fatalities, but more efforts are needed to ensure safe passage for panthers across an increasingly developed landscape.

Additionally, habitat fragmentation leads to genetic isolation, which can cause severe health problems within the population, such as heart defects and skeletal abnormalities. Conservation efforts, including past genetic restoration projects, have helped mitigate these issues, but maintaining protected, connected landscapes is crucial for the species’ long-term survival.

While Florida panthers generally avoid humans, as development continues to push into their habitat, encounters may become more frequent. Education and responsible land management are key to reducing conflicts and ensuring the survival of Florida’s most iconic big cat.

Florida panthers are solitary and territorial animals, typically only interacting when a pair is mating or when a female is raising her young. Males require vast home ranges of up to 250 square miles, while females generally occupy 70 to 200 square miles. Males will fight to defend their territory, with dominant panthers securing the best hunting grounds. They communicate their presence through pheromones and physical markings, such as scratches on trees and scent-marking with feces.

Panthers are highly mobile and can travel up to 20 miles a day in search of food or mates. While they are capable of short bursts of speed up to 35 miles per hour, they rely more on stealth and ambush tactics when hunting. Florida panthers are crepuscular, meaning they are most active during dawn and dusk, when their keen eyesight gives them an advantage in low-light conditions.

Though they generally avoid humans, panthers use body language and vocalizations to communicate. Unlike big cats such as lions, they cannot roar but instead make whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. If a panther’s behavior changes in response to your presence—such as staring, crouching, or retreating—it is a sign that you are too close. As with all wildlife, it is important to observe panthers from a distance and respect their space.

The Florida panther once ranged throughout much of the southeastern United States. Due to human growth and development, the Florida panther is limited to just a fraction of its historic range. Now, only a single breeding population survives in the southwestern tip of Florida.

Their current habitat includes the Big Cypress National Preserve, Everglades National Park, the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge, Picayune Strand State Forest, and the rural Florida communities of Collier, Hendry, Lee, Miami-Dade, and Monroe counties.

GPS tracking has determined that habitat selection for panthers varies by time of day for all observed individuals, regardless of size or gender. They move from wetlands during the daytime, to prairie grasslands at night. The implications of these findings suggest that conservation efforts be focused on the full range of habitats used by Florida panther populations. Female panthers with kittens build dens for their litters in an equally wide variety of habitats, favoring dense scrub, but also using grassland and marshland.

Florida panthers play a crucial role in maintaining the health and balance of their ecosystem. As apex predators, they help regulate prey populations, such as deer, wild hogs, and small mammals, preventing overgrazing and maintaining the integrity of plant communities. This natural balance supports a diverse range of species that rely on healthy habitats for survival.

In addition to population control, panthers indirectly influence scavenger species like vultures, raccoons, and coyotes, which benefit from leftover carcasses. Their presence also impacts prey behavior, encouraging natural movement patterns that prevent overconcentration in one area, reducing habitat degradation.

Because Florida panthers require large, connected landscapes to survive, their conservation benefits a wide range of other wildlife. Protecting panther habitat ensures the preservation of Florida’s forests, wetlands, and grasslands, safeguarding the rich biodiversity that depends on these ecosystems. As one of Florida’s most iconic and endangered species, the panther’s survival is a strong indicator of the overall health of the state’s natural environment.

Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi)

Kingdom: Animalia – Encompasses all animals, excluding plants and microscopic single-celled life.

Phylum: Chordata – Organisms with a spinal cord.

Sub-phylum: Vertebrata – Animals distinguished by having a backbone.

Class: Mammalia – Warm-blooded vertebrates that produce milk for their young.

Order: Carnivora – A classification based on anatomical traits, though diets may vary.

Family: Felidae – The scientific category for all cat species.

Genus: Puma – A genus that includes cougars, pumas, and mountain lions.

Species: concolor – Meaning “uniform in color.”

Subspecies: coryi – A classification specific to the Florida panther population.

Florida panthers are carnivorous and primarily hunt white-tailed deer, wild hogs, raccoons, armadillos, and smaller mammals. As opportunistic predators, they adapt their diet based on prey availability, occasionally consuming birds, reptiles, and scavenging carcasses when necessary. Their hunting strategy relies on stealth and ambush, using their powerful hind legs to leap and take down prey with a swift, decisive attack. Panthers are most active during dawn and dusk, using their keen eyesight and hearing to locate prey.

Because panthers require large home ranges to find enough food, habitat loss can make hunting more difficult, leading to increased competition for resources. While deer and wild hogs make up the bulk of their diet, smaller prey like raccoons and rabbits become more important when larger game is scarce. As top predators, they play a key role in maintaining balanced ecosystems by regulating prey populations and preventing overgrazing, which helps sustain the overall health of Florida’s wildlands.

Mating season for Florida panthers occurs from October through March, with most births taking place in the spring. Female panthers reach maturity between two and three years old and have a three-month gestation period. They typically give birth to one to four kittens in a secluded den, often located in dense thickets or dry, protected areas.

At birth, panther kittens are blind and covered in spotted fur, which helps them blend into their surroundings. The mother remains in the den for about two to three weeks, nursing her young and only leaving to hunt. The kittens stay in the den for around two months before beginning to follow their mother on hunting trips, where they learn essential survival skills.

Young panthers remain with their mother for about a year and a half before dispersing to establish their own territories. Males tend to travel farther than females in search of unclaimed land. In the wild, Florida panthers can live up to 12 years, but their survival depends on the availability of habitat and the ability to safely navigate human-dominated landscapes.

Photos courtesy of Jay Staton | Panther Cams

How to Help

Florida panthers are a vital part of the state’s ecosystem, playing a crucial role in maintaining healthy prey populations and supporting the balance of their habitats. However, habitat loss, road fatalities, and human-wildlife conflicts continue to threaten their survival. Without dedicated conservation efforts, the future of Florida’s only big cat remains uncertain.

You can help by:

- Donating to FWF to support land conservation efforts that protect and restore vital panther habitat.

- Educating your community on the importance of coexistence and responsible land use to reduce human-panther conflicts.

- Advocating for wildlife-friendly infrastructure, such as highway crossings and protected corridors, to ensure panthers can safely navigate their shrinking habitat.

Latest news about the Florida Panther

Florida Panther F.A.Q.s

Why are Florida panthers important?

The Florida Panther is an umbrella species, which means they are the heart of the ecological community within their habitat. Protecting panthers in Florida indirectly conserves other threatened and endangered wildlife in the state.

How many Florida panthers are left?

Today there are an estimated 120-230 Florida panthers left in the wild. They are found in southern Florida in swamplands such as Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve. The subspecies is so critically endangered that it is vulnerable to just about every major threat. The Florida panther is currently listed as endangered and is protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Are Florida Panthers aggressive?

Florida panthers are not aggressive toward people. They are elusive, solitary animals that prefer to avoid human contact whenever possible. If given space and respect, they pose little to no threat. In fact, Florida panthers are far more threatened by humans than the other way around—habitat loss and fragmentation due to development have pushed them to the brink. It’s also worth noting that there has never been a documented Florida panther attack on a human.

What can you do if you encounter a Florida panther?

Encounters with Florida panthers are rare. But if you live, work, or recreate in the panther habitat, there are things you can do to enhance your safety and that of friends and family. If you encounter a Florida panther in the wild, make yourself appear larger, avoid crouching or bending over, do not run, and give the panther an easy way to escape.

When it comes to personal safety, always be aware of your surroundings. Florida panthers are most active at night. Exercise more caution at dawn, dusk and during the night, and never approach a panther.

Most panthers want to avoid humans. Keep children close to you, especially outdoors between dusk and dawn. Educate them about panthers and other wildlife they might encounter. Give a panther the time and space to steer clear of you and always hike, backpack, and camp when in wild areas with a companion.

If you live within the panther habitat, remove vegetation that provides cover for panthers. Remove plants that attract wildlife (especially deer). By attracting them, you naturally attract their predator— the panther. Deer, raccoons, and wild hogs are prey for the Florida panther. By feeding deer or other wildlife, you may inadvertently attract panthers. Wildlife food such as unsecured garbage, pet foods, and vegetable gardens also may attract prey. Roaming pets are easy prey for predators, including panthers. Supervise pets and bring them inside or keep them in a comfortable, secure, and covered kennel. Feeding pets outside also may attract raccoons and other panther prey. Where practical, keep chickens, goats, hogs or other livestock in enclosed sheds or barns at night.